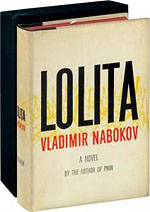

I just finished reading Lolita; it was my first time reading it, but it was not my first Nabokov novel (having already enjoyed Pale Fire and Ada or Ardor). It was a 1955 American hardback edition, the first year Americans got their hands on the book. I don’t understand why anyone buys new classic books in any format — paperback, hardback, or ebook — when beautiful and historic hardback copies can be easily purchased online for a fraction of the cost of buying a new copy.

Nabokov is a staggeringly good writer, in both style and substance. Every sentence feels like a gift from the author to the reader. In the delivery of a gut-wrenching and thrilling plot, he draws you in, deeper and deeper, with his beautiful and astonishing use of language and dramatic structure. I flew through the final 100 pages of Lolita on a flight back from Amsterdam, and it must have been amusing, or perhaps disconcerting, to my fellow passengers to see my face, enrapt, my expressions shifting repeatedly from intense concentration, to a state of near-tears, to knowing giggles, repeat, repeat, in a determined sprint to the conclusion.

(It may strike you as crass for me to consider running a race a suitable metaphor for reading a great book, but please understand that for me, as an athlete, finishing a race is not the end of an ordeal but a supreme pleasure.)

And what delight as, finishing the third to last, right-side-facing page, I turned to the final spread, one-and-one-half pages of text, and unexpectedly found some of the most heartbreaking words of the whole novel, right at the top of the penultimate page, the finish line within sight: an experience that was both textual and physical in its manifestation. Was it the author, the typesetter, both, or neither, who constructed — designed — this neat, sublime, perfectly-timed emotional jolt?

Throughout the final terrifying third act of the book, Nabokov knew that the reader would be constantly, sometimes consciously, sometimes not, seeking (or deliberately avoiding seeking) a single word, a word whose distinctive typographical form would light up like a flare in the reader’s peripheral vision, paragraphs in advance, impossible to miss. Every time you turn a page, even if you avoid it, your eyes will, in an instant, claw through the one-thousand characters in every new two-page spread to find it, the word, the single characteristic letter. He plays with this visual expectation so thoroughly — torments the reader, in fact — that it’s inconceivable that he wasn’t always thinking about printed words, words on pages being turned in a reader’s hands.

Oh, how glad am I that I was unable to find Lolita in any sort of eBook format.