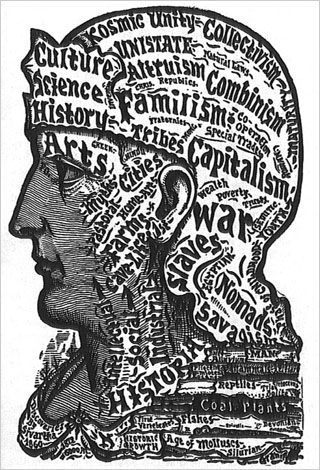

Phases of History “brain map” from the unfailingly astonishing Bibliodyssey.

On the way to the office yesterday, an awesome idea popped into my head. I was in a mad rush, late for an internal team meeting. So I tried to think of effective ways to record the awesome idea besides stopping and writing it down on a piece of paper.

I considered emailing it to myself on my iPhone, but thought that that, too, would slow me down.

I thought about leaving myself a voicemail, but then I thought no, this idea is too awesome to bury in a voicemail I’ll never listen to — I wanted it handy and in my face later in the day.

Then I thought about all the different iPhone apps that could help me, especially voice recognition applications.

I thought about how a few years ago on this blog some ill-informed commenters theorized that speech-to-text was a hoax, that such systems were being powered by low-wage english-speaking human beings who literally transcribed recordings all day long.

After all that thinking, guess what? I forgot my awesome idea. I arrived at the office door and stood there sifting through my brain and finding nothing. But I knew the idea was there. And I knew it was awesome!

The Mister Spock Method

So I left the office and retraced my steps, basically blowing off my meeting (sorry Behavior colleagues!), determined to recall the awesome idea. My wife calls this the Mister Spock Method, although I’m not sure I recall the episode where Spock has an awesome idea but forgets it.

I walked three blocks back towards the subway station, digging through my brain every step of the way, and continually coming up with nothing but either (a) ruminations on how ideas come and go, or (b) more thoughts about speech recognition. Damn!

But then, at almost the same location where the awesome idea first struck, I saw something interesting and thought, “I’d like to take a photo of that right now.” Which was exactly what I thought ten minutes earlier. The awesome idea came back to me, all at once, in a flash.

The Memory Hole

Once upon a time, human beings had amazing memories. Because writing materials were so expensive, and literacy so rare, people who needed to move knowledge through space and time had only one option: their brains.

Today we can’t remember even a simple phone number, yet only a decade ago most of us could recall dozens or even hundreds. All because a technology (speed dial) has replaced that portion of our cognitive burden. Search engines guarantee that we don’t need to remember anything, since we can always just Google it. Some say that this makes us mentally more powerful than our predecessors because we are able to use our brains for new kinds of ideas instead of wasting so many brain cells on dumb information storage and retrieval.

But is this actually a burden? I don’t think so. My grandfather, who was in his second career an English teacher, could recite hundreds of poems and passages from literature from memory. I liked to think that the fact that this “content” existed in his mind (and was readily accessible thanks to his deliberate memorization) made his inner life richer. I also imagined that poetic words and phrases and stylizations would find their way into his own writing, and even into his dreams.

Looking back on my lost awesome idea yesterday, I can see my mistake: I had immediately ruled out writing the idea down. I disarmed myself of the most powerful mnemonic tool in my kit. I thought about bells and whistles instead of pen and paper.

Outside of language itself, writing and drawing are humanity’s most fundamental information technologies. These three technologies are the closest we have come (so far!) to perfecting “the human interface”. In fact, speaking, writing, and drawing are such efficient interfaces to direct cognitive experience that they can, as Andy Clarke has argued, be considered cybernetic extensions of our minds. There’s no doubt that saying something, or writing it down, helps you think more about it and allows the idea to become, like my grandfather’s memorized poetry, part of your on-board memory.

So it worries me deeply that I actually considered using other, less efficient (but more sexy and novel) tools at all. I suppose the reason why I champion sketching so much is because I am so frequently tempted by technological solutions.

I wonder how many people have made this kind of decision permanently, who have effectively decided to use technological tools for all their short- and long-term memorization needs. And I wonder how this kind of society-wide behavioral change has affected our ability to think and produce new ideas.

Comments

12 responses to “Totaled Recall: How technology is ruining our brains”

We are so overwhelmed with information and ideas today, that, in my opinion, the only way to not completely lose our minds is to write things down. When an idea strikes me, it’s usually while I’m thinking about something totally different. I am not able to use the idea right away, and since my mind is busy with something else, I prefer to write it down and take a look (and think) of it afterwards.

There’s another aspect of your observation. Most people I know don’t use technology that intense, hence they still rely on their memory. As for the rest of the people – the more “tech-savvy” ones – their brains function in a totally different way. They are capable of processing a lot more information than the non-geeks. And still, they use their memory quite a lot. I am tempted to cite Einstein here: when asked about the speed of light, he kindly answered (citing from memory) “I don’t make an effort to remember numbers I can find in every book.” And you’d agree Einstein didn’t lack his ability to think 😀

RE: “I liked to think that the fact that this “content†existed in his mind (and was readily accessible thanks to his deliberate memorization) made his inner life richer.”

…from my own experience as a well-read and curious person, I’ve always known this to be true. Nice to know I’m not alone.

I feel like some of this is less about the act of writing and more about immediacy. Plenty of people used micro-cassettes as a method of note-taking because they disciplined themselves to using and reviewing audio cassettes for this purpose. Writing is more immediate for everyone because we all learn paper note-taking, but that doesn’t mean other methods can’t work as well, so long as we commit ourselves to using that method, and that media we use with it doesn’t have any cruft that gets in our way during the process (especially in digital form, like a warm power-up for a PDA vs. pressing record on a cassette recorder — i’ve lost my train of thought browsing through a menu trying to find a Note app).

Sorry, I do realize that I only responded to the last two paragraphs of your post :*)

RE: Brian

I think there’s a difference between memorizing certain words and memorizing ideas. Context plays a big role, as well as the utilization of what you’ve memorized.

I have a question for you: How do you learn a foreign language? Do you sit and memorize vocabulary lists, or do you prefer to read & write texts and learn the use, context, etc.?

Some interests can still only be pursued through involuntary memory. When I reread ‘Paradise Lost’ this summer, I found Chaos described as ‘dark and deep’. I realized that when Frost uses those words to describe the woods he stops by on a snowy evening, he hopes to infuse the woods with some of the power of primordial chaos. I’m convinced the diction is not coincidental, partly because Blake uses the same words (though with an ampersand of course) regarding chaos, so there was actually a thread for Frost to pick up. I never perceived this aspect of the Frost poem before, because I did not remember that the phrase appears in Milton.

Often footnotes will tell us about references as we are reading, but if the notes don’t suffice (or better, if we happen to sense a connection no one has written about before, which is part of the thrill of reading poems), then we just have to hope something resonates with our memory.

My guess is that old-style education in poetry with all its memorizing (and all its faults, which were many) actually made the poems better for some of their readers (probably not for everyone) by making it easier for the students to hear echoes as they read further poems.

The whole “Google is making us stupid” idea has been overblown. There’s significant evidence that frequent internet/technology use actually improves our memory, as well as other cognitive traits.

http://www.theatlantic.com/doc/200907/intelligence

http://www.apa.org/releases/youthwww0406.html

http://www.newsweek.com/id/163924

@Brian Potter @Rumena: I agree that there is a lot of upside to computer use and that the Google makes us stupid concept is very much overblown, especially when we’re talking about computers being used by people who know what they’re doing.

That said, there is still so much poor user experience design and crappy usability out there, and yet so much seductiveness in technology, that I cannot have faith that all technological solutions are beneficial enough that it’s worth putting aside the old techniques.

I cannot, for example, agree with Einstein’s otherwise-reasonable dictum (Quoted by Rowena, above) when it comes to things like poetry or philosophical ideas — just because I can at any time use the internet to look up a Shakespeare sonnet or re-read Immanuel Kant doesn’t mean I cannot benefit immensely by having their words and ideas memorized in my brain at all times.

The Amish are widely misunderstood as the equivalent of technology-hating luddites. They are, in fact, highly appreciative of technologies, but only when evaluated and determined to be a net benefit to the things they value most in their culture: family, community, and friendship. This is really what I am getting at: a pen and paper are still more powerful, in many cases, than any existing digital interface around when it comes to thinking through and recording ideas.

My dilemma is that as a user experience designer I have to at least try new digital user experiences even when they suck and are actually inferior to lower-technology solutions.

Paper is great! Never “crashes”, the batteries never die, it’s biodegradable, never needs an upgrade, and is widely available. Best yet, it’s a renewable resource. Are iPhones a renewable resource?

… so what was the awesome idea?!?

Sorry, mate, but I think your logic is reversed. Before people had memory aides, they didn’t have better memories, they simply forgot things. This is the reason why the rate of innovations has increased rapidly since the advent of literacy, and even more so since the information age started.

Your average talented person wasn’t any smarter then than now– they just had better tools to work with. And that includes recording devices.

@Jack: I pretty much agree with you, except for one thing: Memory is a fluid human capacity.

Memory is something we can deliberately use. We can make an effort to commit things to memory. We can practice and learn mnemonic techniques to remember things. We can improve our memories through practice.

If memory skills can be cultivated, and if technology makes that cultivation pointless, then it is only natural that people will stop bothering to cultivate memory.

So I agree, memory is not atrophying and technology isn’t making people’s memory worse. But I stand by the assertion that exceptional memory skills are becoming less common. Bit of a nuance there, and you are correct to note that nuance is needed here.

Another way of putting it is using your words: Tools. The tools they used were mental techniques, and now we use pens and computers. I am not overly praising old-fashioned “natural” memory tools: I recognize that computers are definitely better. I just wonder what the side effects are, again citing the example of my grandfather in an idle moment having access to things that folks like me need a computer for. When the internet is accessible to my cerebral cortex directly, all bets are off, of course.