Let’s say you own a big building full of valuable stuff. How do you make sure that the night watchman patrolling your factory floor or museum galleries after closing time actually makes his rounds? How do you know he’s inspecting every hallway, floor, and stairwell in the facility? How do you know he (or she) is not just spending every night sleeping at his desk?

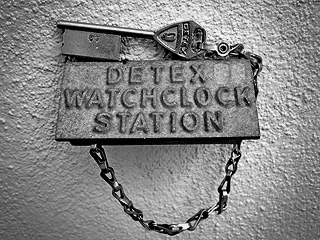

The Detex Newman watchclock was first introduced in 1927 and is still in wide use today.

If you’re a technology designer, you might suggest using surveillance cameras or even GPS to track his location each night, right? But let’s make this interesting. Let’s go a century back in time to, say, around 1900. What could you possibly do in 1900 to be absolutely sure a night watchman was making his full patrol?

An elegant solution, designed and patented in 1901 by the German engineer A.A. Newman, is called the “watchclock”. It’s an ingenious mechanical device, slung over the shoulder like a canteen and powered by a simple wind-up spring mechanism. It precisely tracks and records a night watchman’s position in both space and time for the duration of every evening. It also generates a detailed, permanent, and verifiable record of each night’s patrol.

What’s so interesting to me about the watchclock is that it’s an early example of interaction design used to explicitly control user behavior. The “user” of the watchclock device is obliged to behave in a strictly delimited fashion.

But before I go into the interaction theory at work here, let’s look at how the watchclock system works in a little more detail. The fundamental innovation — the trick, if you will — is that the device itself is only one part of a larger, external system.

Photo by Jeremy Brooks.

The Key is the System

The key, literally, to the watchclock system is that the watchman is required to “clock in” at a series of perhaps a dozen or more checkpoints throughout the premises. Positioned at each checkpoint is a unique, coded key nestled in a little steel box and secured by a small chain. Each keybox is permanently and discreetly installed in strategically-placed nooks and crannies throughout the building, for example in a broom closet or behind a stairway.

The watchman makes his patrol. He visits every checkpoint and clicks each unique key into the watchclock. Within the device, the clockwork marks the exact time and key-location code to a paper disk or strip. If the watchman visits all checkpoints in order, they will have completed their required patrol route.

The watchman’s supervisor can subsequently unlock the device itself (the watchman himself cannot open the watchclock) and review the paper records to confirm if the watchman was or was not doing their job.

This is an idea with long legs. The watchclock is built like a revolver, of good old fashioned brass and steel and encased in a thick leather holster. It requires no batteries and almost no maintenance. The “guard tour patrol system” concept, too, has a timeless elegance. The mechanism itself has barely changed for a century: although some more recent models incorporate GPS and other technologies, the mechanical key-based watchclock system is still in wide usage, with many buildings still employing the same keys and the same clockwork devices they’ve used since the 1940s. It’s a genuine example of an “if it aint broke, don’t fix it” kind of technology.

From a behavioral perspective, I find the watchclock fascinating not simply because it’s a kind of steampunk GPS, a wind-up mechanical location-awareness technology. I’m further fascinated at how this holistic system of watchclocks, keys, guards, and supervisors succeeded so completely in creating a method of behavioral control such that a human being’s movements can be precisely planned and executed, hour after hour and night after night, with such a high degree of reliability that almost a century goes by before anyone thinks of ways of improving the system as originally conceived. The watchclock is a primitive form of technology-mediated interaction design and narrowly-focused social engineering: The “interface” is the whole system: The watchclock, keys, and paper records.

Designing for Control

Many in the interaction design field(s) argue that user experience design most definitely is not about behavioral control, or at least it shouldn’t be. Dan Saffer entitled his excellent book “Designing for Interaction“, the “for” being a nod to the idea that users don’t need to interact with systems in exactly the way the interaction designer intended or envisioned. Interactive systems — whether social networks, desktop apps, or multiplayer online games — often shine best when users break the rules. Systems that explicitly and deliberately give users the freedom to interact in creative and unforeseen ways are some of the most interesting and powerful kinds of interaction design.

But the watchclock is another kind of interaction design, one whose function corrals the user into a single, linear, constrained sort of behavior. The night watchman has a fundamental social constraint — the desire to not get fired from their job. This constraint allows the watchclock patrol system to work so effectively (some would say insidiously) as an interaction design instrument of control.

As a former game designer, I think it’s important to recognize that a really fun user experience will often exist somewhere between these poles of freedom and control. The player can kill the bad guys in whatever clever way she wishes, but she’s got to collect the three crystals to operate the teleporter — there’s no other way off the ship, and no other way to get to the next level. (I wonder if it’s more than a coincidence that so many systems of controlled-play in games involve the use of keys, just like the watchclock.)

Giving a user freedom to interact however they wish seems admirable in principle, but requiring the user to jump through precisely the hoops you, the designer, want them to jump through is also a powerful way to create an emotionally and intellectually compelling experience. In a practical sense, it’s also a way to make sure that the user doesn’t get frustrated or even fail to do what they really need to do.

The watchclock’s user experience isn’t compelling or stimulating, to be sure, but in my mind it is truly an archetype of the “behavioral control” side of interaction design.

Comments

39 responses to “Who Watches the Watchman?”

By the way, there are direct, modern equivalents to this system. In our building, small tags are bolted to strategic points that late night patrol staffers must touch an electronic wand to, confirming they passed by. One such tag used to be directly behind my old desk. The system was installed a few years after I arrived, and it’s been fascinating to see the complete change in their patrol patterns and behavior that its definitely dictated.

While I understand the value in creating flexible systems that allow users to approach them in their own way, I think we as interaction designers are kidding ourselves if we think our work doesn’t ultimately boil down to controlling behavior. The way we help people accomplish tasks is by limiting their options, by filtering their experience in a valuable way. No one system works for everyone, of course, which is why we aim for flexibility. The goal is to find the right balance of open and closed.

A variation (and the dual of this design) is to let the watchman carry a single key and visit several wall-mounted clocks instead. This is more expensive – keys are cheaper than clocks – but potentially more secure, as the clocks can not only record when they were reset but also signal an alarm if the watchman did not arrive to them in time (in case he was assaulted, say).

An arrangement of this type is shown in Fritz Lang’s brilliant film ‘M’ (1931).

An easily defeated system. What happens is that guards detach the keys and bring them back to the guard station and punch them there. Saves a lot of walking.

@bc

he’d have to walk to each station get the keys, and then at the end of his shift go and put them all back, this assumes his supervisor will periodically check the keys are in their correct location. so walking his route at least twice a night may not save that much effort, depending on the length of time it takes to do it once.

We used a Detex for watch duties when I was stationed in Galveston TX in the Coast Guard.

One week we got the bright idea of using a bicycle to run the route quickly and turn the rest of the watch into a nap.

That lasted for about 4 days until the security officer quickly noticed that doing the 2 mile circuit was talking about 15 minutes. That put an end to that.

They’re pretty solid little devices. Sometimes simpler is better.

Great point. “An interaction design instrument of control” is obviously what makes this system successful, like good game designs.

Maybe by limiting choice and avoiding the paradox of choice (where by too many options create paralysis) we are actually improving the user experience.

When theses systems are designed well (i.e. game design), this type of controlled experience can provide a truly rewarding “in-the-moment” experience.

As interaction designers, if we can reduce user stress (by limiting choice), and enable users to achieve a rewarding in-the-moment experience by controlling behavior, that would be quite an achievement for any product, system, or service.

I wonder if more “behavioral control” in software and web design today would produce a bit more happiness or at least success?

I read the children’s book “Corduroy” to my son almost every night. I always wondered what the canteen-like thing was that the night watchman in the story wore slung over his shoulder. Cool.

I know this story is really about interaction design in terms of behavior control, but about the watchmen’s clock: doesn’t this clock force the watchman into a rigid set of behaviors in a rigid timeframe? Wouldn’t this make the system MORE vulnerable to attack — for example, a burglar could easily discover the watchman’s rigid schedule and break in to one part of the factory when the watchman is on the other side of the building at a certain time every night.

@Gene: The keys indicate where someone is, not when, so the intruder would have to get their hands on the actual paper card (that not even the watchmen can access) in order to know the route in terms of time, direction, and frequency.

It does imply a single route that could be exploited, but this is not necessarily true; There could be multiple routes, with different key sequences. Or that, while the watchmen must do a route, there could be multiple routes to choose from in order to pseudo-randomize the watch. Or cases where 2 watchmen, going in opposite routes, must meet at the same place at the same time to check up on each other…

In practice, I have seen several devoted watchmen frustrated by these systems. They wished to vary their routes often, and their bosses valued varied routes—but valued them less than the hassle of fiddling with the technology.

I own one of these mechanical clocks, as well as a set of station keys and was also fascinated by the design. It still works and keeps reasonable good time after years on no maintenance.

A few bullets:

* There is no ink to replace (in case that wasn’t clear), the key punches into the paper (but not quite through it).

* The clock also makes a punch in the paper when when it is opened by the supervisor’s key, an interesting detail.

* 24hr paper dials, and the watch can run for 72 hrs (if I remember correctly) without re-winding

* The two “DETEX”s in the center of the paper wheels are cutouts and the clock has matching studs, making it harder to make your own recording disk (DRM or anti-forgery?).

* Having looked at the chains the keys are attached to, I think it would be difficult to remove the keys and put them back again without anyone noticing.

I worked as a security guard my first year of grad school and used a watchclock. One problem with the system is that it reinforces the same pattern and same pace of patrol, one that could be learned by an intruder.

And the pattern becomes rote after a while, so it’s possible to do it without thinking, much less watching for problems. I sometimes thought a randomly-placed “problem” along the route would have been better to keep us on our toes.

It satisfies the bureaucracy; the supervisor can prove to his supervisor the guards were on patrol.

And it did make a satisfying “ka-chunk” when the key was turned.

Robert Fabricant has been seeking this balance as well:

http://designmind.frogdesign.com/blog/behaving-badly-in-vancouver.html

I have to wonder just how well these keys worked at preventing criminal activity that utilized an inside man?

Not at all, most likely.

Counterfeit keys would have been easy to produce and used to “prove” a watchman was on his appointed rounds, when he was helping confederates enter a building at another location.

Why wouldn’t a guard make a mold of each key, thus making his own master set of keys on a ring he keeps with him?

The guard pulls the right key from his ring per the scheduled time and not leave the guard desk. I wonder how many people did that.

Any photos of a paper disk marked by the keys? Is it punched or marked?

Does the key wind the clock to keep the clock running?

It’s still a fascinating machine and I am going to have to go do some research now. Great article. Thanks!

My girlfriend is majoring in Radio/Television/Film and as part of one of her film courses she had to watch this old silent (but subtitled) German movie (the title escapes me). In the movie, criminals decide to go vigilante against some child murderer because the heightened police presence from his streak of murders isn’t good for their business. They finally track him into some office building and take the night watchmen hostage while they search the building for the murderer.

The building had one of these systems, and the criminals went to great lengths to make sure to keep putting the keys into each of the stations because failure to do so would sound an alarm and alert the police. I thought the system was kind of fascinating, but hadn’t thought about it since until this post.

@Zachary Danger: As Mattias EngdegÃ¥rd mentions in his comment closer to the top of the page, “An arrangement of this type is shown in Fritz Lang’s brilliant film ‘M’ (1931).”

Thanks for the nostalgia.

I remember seeing these stations all over the schools I attended growing up. I had an idea of what they were for, but never knew the details. In fact, I believe I saw one of the “canteens†in a storeroom one year during my summer job.

@Gene

You make a very good point. However, the burglar would not be required to exercise even this rudimentary level of ingenuity were the watchman off sleeping somewhere. Within the limits of the technology available at the time, this was a way of insuring at least a minimum degree of security for your site. I do suppose they could perhaps vary the sequences or timepoints from night to night.

I used this system at various locations when I was a Pinkerton during college. Having a set route was considered more of a feature than a bug. As long as the route was comprehensive enough it was considered saitisfactory. Half of the point of the route was just to keep the guards on their feet and awake.

The job of a night watchmen isn’t to prevent break-ins or theft, it is to witness and report such crimes to the police in a timely fashion, hopefully in time for the transgressors to be caught or at least scared off.

As for the possibility of rigging the system- I don’t think so. The majority of my fellow guards were bright in enough in one way or another, but lacked the , uh, initiative to plan and execute a method of fooling the watchclocks.

Professional burglars love these systems; it makes getting in and out without being caught a lot easier. Watching from a parked car a safe distance away, observe the watchman – every time you see him retrace his steps you’ve identified a key location. Measure the time it takes before he returns to that key and you’ll know how much free time you can have in that area because you know the watchman will be somewhere else. You also know that those areas aren’t equipped with alarms so it’s going to be easy pickings.

This looks to me a lot like a technologisation of some of the systems that were used, in the C19th in the UK at least, to keep police on their beats. The main one was a set of hightly detailed beat instructions, specifying where each man had to be every five minutes. The inspection regime was carried out by a patrol sergeant who would require an explanation if a man did not arrive on time. In more dispersed areas, beats were managed by the men meeting up on their boundaries at ‘conference points’: the conference needed to be recorded in each man’s notebook.

During the first half of the C20th, street police telephones were used a lot for this purpose: cops had to ring in at certain times to make it obvious that they were where they needed to be.

Yes, it’s as Foucauldian as it sounds.

Once radio took over, in the 1960s and 1970s, a lot of effort was put into automatic vehicle location systems, so that car 54 couldn’t hide from the control room. Most of these then morphed into the first generation of mobile data links.

As you might have twigged by now, I’m writing a book about this. The clock is great – thanks for writing about it.

Our clock worked, sort of.

When our ship was in port we hired a night guard to make sure the ship didn’t sink. The guard didn’t raise an alarm, but complained the next morning that she had to wade through water to get to that key!

Cold water evidently not enough to wake her up from that rote zombie watchclockwalk.

There’s a little black box in the stairwell of my building that I had heretofore wondered about. It’s empty with a small hook inside and something about watchmen on the cover. Thanks for posting this, I can’t wait to tell everyone at work that the mystery has been solved. -)

The modern, electronic equivalent to watchclocks.

http://photo.transmit.net/picture/px10216-lg.html

http://www.deggy.com/

I was tethered to one of these doing firewath in a huge Sugar making plant in early 70s. My way around half my route was to take the keys off the posts and take them with me to a nice, hidden, warm place on top of the buildings that I turned a key whenever I thought I could stretch it to. I then put the keys back at end of night. On a 35 minute round I was legitimate on maybe 10 minutes.

The film NIGHTWATCH (not the Russian fantasy but an earlier film) uses these clocks to create tension. The lead character is a watchman in a morgue and must make rounds using one of these devices. One of the keys is at the back of a room filled with corpses and makes for several chilling scenes.

There is a fine line between effective system/behavior management and controlling to the point of hamstringing your employees. But as long as you used a system that allowed for a randomized order of station check-ins/routes from night to night and prevent “sleepwalking” and thieves using the system, why not use such an ingenious system?

Anyway, if there IS something wrong and the guard is forced to deviate from his route, the supervisor will be informed and forgive the changes noted by the system.

MacDonald’s have a similar system, modernized. Whoever in the crew is assigned routine ‘front of the house’ maintenance carries a fancy PDA type device around, and touches it to various key locations throughout the site. For example, there might be one at the back of one of the garbage boxes, and the intent would be to date/time stamp the visit to check that the garbage is emptied or at least tolerable. Another would be inside the restroom, or at the condiment rack.

I’m not sure if it’s everywhere, but I’ve witnessed it in action in North Vancouver, at the corner of Marine Drive and Pemberton, if anyone’s obsessively interested …

As a night security officer at a small private university, I know this system would not work on our campus. It is probably more ideal for one contained building. Most of my trespassing arrests have been made when I was in a random place at a random time. We have a dispatcher to record our checks via radio, though, and this leaves a lot of leeway for slacking!

Note to ambitious people: Sounds like you could make a fun game of Scavenger Hunt / orienteering / AR with these devices.

Perhaps the guard could be carrying one key for several key-receivers throughout the area. If each receiver is not “unlocked” for x minutes (where x is the amount of time to make a round) then the alarm goes off.

Wouldn’t this system dehumanize the nightwatchman by turning him from a man trusted with the security of your assets into an untrustworthy cog in a machine ? I could see myself putting a lot less effort in if “guarding” turned into “tedious race from checkpoint to checkpoint.”

you might note film’s most enduring portrayal of the clock in Fritz Lang’s M

Watchman is so exciting.

I’m looking forward to the movie.

Really good post. I find a lot of online tools lacking the simple basics of good, old innovation.

i liked the way you observed something and then generalized it into ‘behavior control’. what many commentators above did not get was, this post was not just about watchclocks, it was about a different way of interactions. while most design looks at human behavior and designs according to it. in this case it is the opposite, designing so as to control behavior.

again, great observation!

Hi. when i was a kid, i knew a night fireman at a HUGE 3 story furniture factory up north. (l.z.kammens, there i said it) Anyways, i was 15 and would “hang out” as i was bored. there was killer playboy and hustler mags in the bathrooms, and we would start up various machines at night and make things, feed the hog to fire the boilers to make the steam, the HUGE 2 story compressors, the blowers that had a foot long START lever you had to really pull just right and hold for 30 seconds while the whole thing wound up like a jet engine. Thrilling, i’ll never forget the sound. I also learned his watch route doing the hourly rounds on this, i dont know… 10 acre building site including offices, shipping warehouses, every part of the place. we had a ring with like 30 keys and i learned them all. there were like 17 stations and i learned those too. i would do rounds while “joe” would sleep, study, what not. we’d take turns riding across the long shop on product conveyer belts. i’d jump off, turn it off for joe, he’d get on the next one, I’d turn it on, and then jump on, ride along, jump off to key the clock, jump back on… Oh the fun we had. I dropped the clock and broke it one night. We went about 6 weeks with no clock while it was repaired. joe was mad at first, but very soon quite happy with the accidental “break”. After another few months and i ended up accidently feeding a huge die into the hog, almost ruining a $150,000 dollar machine. It caused $12,000 dammage in less then a minute before spitting it back out and ruining a workbench and light, missing me by 3 feet as i was trying to shut down the machine. a week later joe was canned. i cried all week. GOD i had fun there. the place closed not long after and burnt down in 93 or 94. another sad day for me. i really loved that place. I just found a simplex watchclock, made also in my hometown, gardner, mass. I worked there too (legally) making timeclock parts and fire alarm boxes, but never knew we made watchclocks. it has no keys, but has the leather case. If anyone knows anything about it or can shed some light on it, please send a thread or get back to me. bye.

Back to the thread. i really dont know how joe didn’t get fired earlier on as he was never very specific with me on the rules. I know i often missed a few stops here and there and messed around a LOT between rounds as i never realized the importance of it. it was just a game to me. So, his superviser must not have really cared much is all i can think. i can only remember him telling me he almost had to pay the repairs to the clock but never mentioned any of the missed stations. funny. I look at this system as a very creative way to make sure your employee keeps an eye on the place. i don’t think it matters much if you change the route, as long as the keys are all hit each round at some point. i guess it depends on what you are protecting, from whom and how much money ya got to keep it protected with. i dont think Fort Knox would use the same type of system. i think it was great for a furniture factory though. but then, what do i know? i was working there illegally for almost 6 months and was never discovered. i STILL wonder how that freakin die got in there, it was a good 20 pounds and i HAD to have shoveled it, no other way. i’m still befuddled, 25 years later. it was most definately an accident. i wasn’t a destructive kid.