Debating the merits of competing design ideas is fun and, as I’ve argued in parts one and two, can be extremely productive. But some design disputes are, I think, unanswerable. And it’s important to realize when a debate has crossed over from something you can resolve to something you will never reach any definitive conclusion over. Matters of personal preference, style, and taste.

Any given product or application’s appeal and usability success, or lack thereof, might ultimately come down to each individual user’s personal taste. There is a broad landscape of different approaches to UI and UX design, and the variance often adds up to a question of style — not of simple “good” or “bad” design principles.

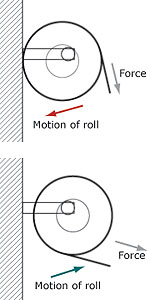

The eternal which way to roll the toilet paper controversy, and the more academic terminal serial comma debate both come to mind, where empirical measures of success may indeed be possible but are nonetheless trivial when compared to what different kinds of people actually prefer. If someone likes their toilet paper oriented the “wrong” way, rolling it the “right” way will utterly fail to satisfy them, even if it makes the TP user experience more efficient in every measurable way.

In short, one can decry the very real and plainly egregious usability violations of any particular design decision, and you can even “prove” you’re right in usability testing. But you can’t argue against real users who actually prefer it any more than you can argue with people who prefer boxers over briefs or blue over red.

This doesn’t mean you simply throw up your hands and give up simply because you can’t please everybody. Because guess what? You can never please everybody.

It simply means that in the design process you have to make a choice to make some people happy and other people not so happy. Of course you can give users options or preferences, making life for both groups a little more complicated. Lots of (inelegant and bloated) products do precisely that.

But you can also choose to declare that your product is just for people whose personal idiosyncrasies and tastes are compatible with the product’s nature. And then you simply write off everyone else, letting the market fulfill their needs with a different product. It doesn’t help anyone to be greedy and try to make the same product work for all kinds of people when you are up against factors that cannot ever be decided. Find these factors as early as you can and make those hard decisions, one way or the other.

[tp configuration images by Brian Mathis, whose opinion, by the way, is just plain wrong 😉 ]

Comments

3 responses to “Adversarial Design, Part 3: Arguing the Unarguable”

Reading this made me think that every one of these arguments can be made about having faith or no. Which makes sense when you consider the Cult of Mac, etc. I know people who can’t stand Justin Long, and feel that Hodgman is the person most like them, the more sympathetic character. Of course, I simply don’t agree with them about the Big Questions of aesthetics either.

This all implies that there is some great Truths out there (or at least great choices), design- or otherwise, and that in the selection of various binaries much other content is encoded in the DNA of various design decisions.

Would you agree? And if so, what are the first binary divides in design?

@raafi: Great observation that preferences and tastes are closely connected to the nature of religious sentiment.

And just as with religious faith, I don’t see what good can come out of declaring a binary right/wrong about one faith or taste choice versus another when it comes to those issues that we can disagree on with no harm done. If people want to pray to sentient pasta, or design their web sites with Comic Sans, what harm is done in that?

Which I suppose leads me to the conclusion that the only important “binary divides” in design aren’t design questions at all, but rather are moral in nature. Fundamentally, it’s “don’t hurt people.”

It seems to me that toilet paper rotation philosophy (and isn’t that the final goal of esoteric BS?) be broken into:

1: direction of movement: how easy to continue? minor here, but proportional in large systems.

2 : accessibility to easy manipulation – minor here, but proportional in large systems.

3 future accessibility; minor here, but proportional in large systems.

4 ease/ smoothness of replacement : my son will attest to the superiority of duple or triplex systems for smoothness, or suave’.

The most prosaic systems can tell us how to Design! Tell me if I’m wrong-OK?