Last.fm‘s announcement that they will be allowing their users to listen to full-length versions of millions of music tracks is one of the final nails in the coffin of the traditional recorded-music industry. Owning music is dead. The new business model for making money in the music industry is simple: Design a better music distribution system. Or, simply put, build a better user experience for music listening.

Which, interstingly, is how the enjoyment of music has always been throughout the centuries, with the singular exception of the century recently passed. Live musical concerts and performances have always been about more than the sounds in your ears: It’s also the experience of the venue, the culture or subculture of the audience, the smells and tastes. This also applies to live radio, including satellite and internet radio. Both live performance and live radio focus on putting value on (i.e., charging money for) the experience around the music — on the curation, the immediacy, the communal feeling of listening to the same music as dozens or even millions of other listeners — not on the ownership of the recording itself.

In fact, the ownership of recorded music will someday be seen as a weird historical anomaly, born during a decades-long spasm of corporate enthusiam about — and complete control over — the production and distribution of recorded music… a phenomenon in its death throes now that, finally, the ability to record, copy, and distribute music has trickled down into the hands of everyday people.

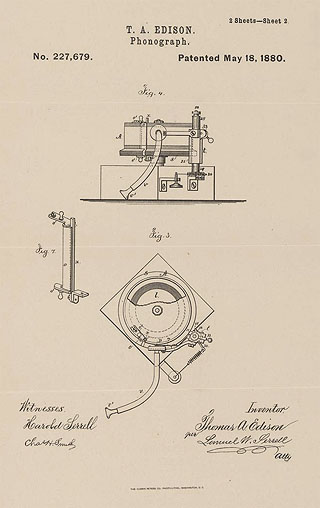

The era in which one could buy and sell recorded music lasted only about a century, from the early days of the phonograph in the late 1800s to the emergence in the 1990’s of illegal file sharing and now, in this decade, completely legal free distribution of recorded music. We are back where we started: paying for experiences, not for artifacts.

Today’s digital music scene is about experiences. iTunes, for example, is not so much a tool for organizing your music collection as it is a complete media experience platform: It’s the tool to listen to and organize your music, of course, but with the store integration, partnership with your portable player, accessibility to other users on your network, sharing with your TV and home stereo system, it’s become far more than a simple media player.

Last.fm takes it further: Are you listening to something you really like, and you want more? Well, right there on the page, the page that is playing the music, are a dozen different ways of exploring that music further: Talk to other fans, read about the band’s history, view recommendations based on your own listening habits, listen to artists that are intimately related to the band you’re hearing, find out about new music that came out just today.

Valuing Media

Kevin Kelly recently wrote a really insightful and thought-provoking piece about how the value of copied media can be measured:

When copies are super abundant, they become worthless.

When copies are super abundant, stuff which can’t be copied becomes scarce and valuable.

When copies are free, you need to sell things which can not be copied.

In the case of music, the “stuff which can’t be copied” is (among other things) live, performed music. Kelly’s piece explores a few other ways that stuff can be valuable without being copyable — it’s a great read, please check it out.

Last.fm actually hits several of Kelly’s values dead-on, including Accessibility (the ability to tune in from any browser and not be tied to your own hard drive), Patronage (the artist is getting paid by Last.fm, something that many listeners want to know is happening), and Personalization and Findability (Last.fm was literally founded on the idea of making new music findable through personalized recommendations).

Rhapsody was on the right track, but their catalog lacks the kind of Web 2.0 community-generated depth and recommendation tools to make listening to and discovering new music such a delightful experience. On Rhapsody, AFAIK, you are renting access to a database that allows basic browsing by artist, genre, etc. That’s it. It’s fundamentally still about paying for temporary ownership of music.

But as I said, it’s not about owning the music any more. It’s about providing easy and fluid access to the music, exposing you to new music you will like, immersing you in a music community, and making the listening experience as entertaining and interesting as possible. Ownership is no longer an issue. Today you pay for the experience of a product which, in the peer-to-peer era, you can always get in raw form for free or nearly free.

In the future competition in the music industry, such as it is, will consist of better and better ways of competing, essentially, with old-fashioned radio, nightclubs, and concert halls. Last.fm gets this.

Comments

22 responses to “R.I.P.: Owning Music (1880-2008)”

Mostly a great article, but your focus on last.fm is missing out on the other, bigger site which really made the big changes in the last year. imeem.com started out at ‘youtube for everything’, except nobody called it that in 2004 because youtube hadn’t been founded. The music feature is what caught people’s attention and after some licensing shenaningans imeem.com has been offering the free, on demand streaming of music way before last.fm made it’s announcement, in fact with no limits and a larger catalog imeem’s service is superior to that of last.fm.

But owning music will take a while to die yet – if you look at imeem one of the most commonly asked questions is ‘how do I download’ the music.

Great read.

The only reason why I still need to ‘own’ music is the lack of easy accessibility of services like Last.fm. I want to listen to ‘my’ music in the office AND in my car AND at the beach, etc. At the moment my iPod can deliver that but once we have internet access everywhere and my devices (may it be a mobile phone or car stereo) can access it easily I will not need my mp3 collection any more. Looking forward to it.

[…] An interesting read on the death of owning music. No Comments, Comment or Ping […]

I’d say the best of music owning is like this also.

Comparing music collections, going round a friends house and browsing and listening to random CD/LPs.

Making mix tapes/CDs.

That’s a good deal of what makes music enjoyable whether you own media with music sitting on it, or you access it directly from an online service.

I also believe that there will always be a niche market for recorded music – so called ‘audiophiles’. As of today, music streamed from last.fm through my hifi is discernibly not as good as the same music from a CD.

I often wonder about much improvement there will be on this. I don’t see websites such as last.fm that stream simultaneously to many users going too far just yet due to bandwidth constraints. Also it just doesn’t make sense when the vast majority of listeners aren’t listening through a hifi but through headphones at work or something similar.

Still, I’m sure this is the future, and will soon reach ubiquity. I just hope that doesn’t drive up costs too much for those of us that like to listen to high quality reproductions of music (Classical music at 128kbps anyone?).

@Matt Turner: Hah, I had actually put the words “hanging out and listening to music with friends” in the second to last sentence, but took it out at the last minute. So, yeah, I agree!

@Jonas Woost (and Matt): The quality of files, and the accessibility to them, are both easily surmountable obstacles compared to the ownership obstacle.

Also, we may, for example, be able to downloaded any music we want someday into portable devices for free, but the means of getting to those downloads in the first place will be what we pay for. When the music is free, you can’t say that you “own” it just because you dowloaded it.

you’re right, chris, “owning music” may have just swallowed the poison that eventually kills it off entirely, but i’m with jonas on the portability issues. there are a ton of biz dev deals left to be made, fail, and made again until the right approach is in play and cheap enough/easy enough for the average joe to make a part of their lives.

most americans — let alone global citizens — aren’t techno-gadget freaks like us. i have plenty of friends who are big music lovers that know *nothing* about last.fm, amie street, imeem, etc. is there a big market to support? absolutely. but dead as in d-e-a-d, owned music just isn’t.

the toxic shock of the poison sure is starting to leave nasty marks on the mafioso industry that pimps the product, though, which is cool to watch.

Part of the experience of music is the ownership — or at least it was when music had a physical nature (enjoying the album cover, placing the disc in the tray, etc.). Purely digital music looses this.

Also having a huge selection at you fingertips is great but you also encounter the tyranny of choice. I don’t know if I’d want my music to be purely subscription based for this reason. More importantly there has yet to be a music service that has all the music I want to listen to. Mostly it’s all the top ten and divided my labels, which is an unnatural way to divide music.

I meant to say “divided by labels”

@Colin: Ah, yes, but the curation of collection then simply becomes your personal playlists and favorites. You don’t need to “own” the music to *have* it.

I’m not advocating subscription-based music. I’m beyond that :-). I’m advocating that the music is free, but the way you get to the music needs to step up. You can have a Terabyte hard drive full of music that you never paid for, and listen to it in iTunes and never pay a cent. The music business has to live with that. If they expect us to pay, we should pay for all the other stuff around the music — the recommendations, the access, the immediacy.

As you say, the “top tens” and label-based sorts of music aren’t enough. Offering cool ways to just browse a dumb database, which iTunes is and which last.fm largely is, too, won’t be enough.

They have to do a lot more. They have to do stuff we haven’t even dreamed of yet, like invent software which, for example, chooses which music to play based on what will make us, as individuals, most productive (I just made that idea up — it’s pretty good!). Or make a device that tells you when you are near other people with similar musical tastes. Or a program that lets you easily change the music you’re hearing to tweak it to match your tastes (“loop the guitar solo” or “delete the cheezy rapper from the middle”). The ownership simply can’t be part of it anymore.

@sean coon: You’re right, it’s not dead — it will linger on in various ways for a long time. They’ll milk it for a few more decades, I’ll bet.

The existence of a market for ringtones should be evidence enough that people will pay stupid money for something that in another context might be damn near free. Eve Apple couldn’t resist the opportunity to take ruthless advantage of the very sad ringtone economic ecosystem.

That said, it’s the airtight control over the platform (the mobile phones) that permits the ringtone market to exist, so in a way it proves my point within that microcosm: you’re paying for the ability to use the music on the platform, not to own the music.

[…] Christopher Fahey over at graphpaper.com has an interesting blog post where he discusses the end of music ownership. Last.fm’s announcement that they will be allowing their users to listen to full-length versions of millions of music tracks is one of the final nails in the coffin of the traditional recorded-music industry. Owning music is dead. The new business model for making money in the music industry is simple: Design a better music distribution system. Or, simply put, build a better user experience for music listening. […]

[…] “We are back where we started: paying for experiences, not for artifacts.” […]

As you know, I’ve been reticent to adapt to certain aspects of advances in music technology and culture. And while I hesitate to believe that our future music experiences are so easily predicted, I do have to admit that this article has given me a new perspective on the subject. Thanks for that.

@Rob Weychert: Thanks. Note that I am not making any specific predictions, just a general sense that “ownership” won’t be part of the equation. The range of potential experiences, and how to monetize them, is wide open.

Personally, I am looking for an app that listens to me hum a few bars of a tune, and then it will start playing something that fits what I was humming, using some knowledge of what I generally like as a guideline.

For the majority of people in the 19th century experiencing music rarely meant going to the concert hall or even the tavern (and I’m not just talking about Westerners). More often, it was performing your own music or listening to others in your immediate social group perform music. Having a piano or a pump organ or a guitar or a banjo or a mbira was not primarily about showing your status but expanding your musical experience beyond simply the human voice.

I think in a way we might be coming back to this. People are actually going out to hear music less and exploring music on their own or in small social groups more. I think the future of music is that everyone will be a dj and want access to as much music as possible (not just their own collection but any song or band they’ve hear once or read about) to mix into the constant soundtrack of their lives.

Great post.

Very interesting post.

It’s important to highlight the distinction between music/musicians/artists and the recording industry.

I’m not sure if people think about “owning music” per se. They just own a record or a tape or a cd or whatever–just a physical object–a recording. The musical experience that you describe is separate and can coexist. I think it’s only recently that people have even given much thought to ownership (or not) of the non-tangible music itself (or a digital copy of a recording). I think people value many of the unique qualities of recorded music. How those recordings will get produced in the future is the question. But I think people will continue to happily pay for and “own” recordings.

@tinydiva: I think last.fm is trying to do the digital equivalent of “hanging out with friends and listening to records”, insofar as you can sample playlists and collections of people you consider friends in the last.fm community. Playing musical instruments is, as you say, pretty much dying a slow death that began precisely when recorded music was born. It’ll never die completely, of course, but it will never be like it was in the 19th century and before. The 20th century may have been an anomaly in terms of ownership, but it was clearly a transformational period in terms of where we can get our music from.

I’m in strong support of letting the user have free access to the arts. Museums charge primarily for upkeep, and radio stations provide not so delicious advertisements. Websites provide much of the same, but does anyone question how much those advertisements actually cover? I’m guessing that even with the radio stations, artists are not being paid very well for their air time.

It’s all about pounding tracks into the listeners’ heads so they succumb to peer pressure and go to a concert with friends. This is where last.fm really succeeds, but only for strong advocates of the service. Those with a strong network of friends who actively attend concerts will make a strong impact on the artist in question. It’s only logical to promote the work of obscure artists by making their work freely available to disperse and leave an impact on society. Once the impact has been felt, it’s suddenly feasible to push merchandise that expresses the listener’s appreciation for the band. When will they learn?

[…] Music: I wrote about this in my last post, which is what inspired this one. Music was once something you could only enjoy as a live experience, in the presence of performing musicians. The 20th century brought us recorded music, which could be bought and sold. This gave everyone the idea that music itself could be bought and sold. With the emergence of digital file sharing, this model is being broken down again, leaving us in a place very similar to where we started, with music being un-ownable, but the experience of music enjoyment being entirely sellable. […]

On a slightly tangential note, TechDirt does a good job synopsizing the problems that both the music industry and the press are having differentiating DRM from copyright. Some very good points about the mess we’re in which have resulted from the proto-fascist DRM movement:

See: http://techdirt.com/articles/20080303/141855416.shtml

[…] In addition to a hysterical design concept, graphpaper.com has a cool post by Chris Fahey on the concept of ownership in the media world. […]

Lower the price on SACD and DVD-A discs…improve the selection thereof. I still play the free sampler of Aerosmith rtc. that Rolling Stone gave away years ago on a high end system. Nothing can touch it in classical music either.