There is a great new series on PBS called African American Lives, in which Henry Louis Gates, Jr. interviews nine high-profile African Americans (including Oprah Winfrey, Chris Tucker, and Quincy Jones) about their family histories. I’m enjoying both the historical aspects of it and the technological inspirations I get from it.

Documents and photographs have to be dug up from filing cabinets and flat files, and painstakingly analyzed by researchers.

What’s especially fascinating about the series is the research that Gates and his team did to transform these family histories from simple memories and oral histories into rich, deeply documented epic stories. For each of the nine subjects, they did extensive interviews with living relatives, conducted research into geneologies and historical records, and even did genetic testing and analysis to help fill in the gaps.

It’s a marvel that, even among these families — who all emerged from slavery and extreme poverty — there are such extensive and detailed records in existence at all. What’s more, these records can, through careful research, be cross-referenced with each other, enabling modern scholars to fit the information together like a puzzle to form a pretty detailed picture of the past.

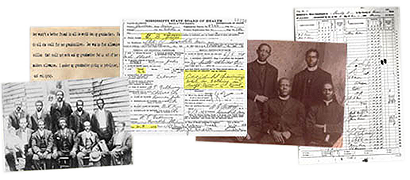

For example, when Chris Tucker was shown the photo on the left, which he hadn’t seen before, and his great grandfather was pointed out to be the gentleman in the middle, he was shocked. I was too! How in the world did the researchers find this photo and know who the person in the middle was? I marvelled at the amount of research that might have been done to make just this one particular cross-reference.

It also occurred to me that this type of research will, in the not-so-far-off future, be a hell of a lot easier to do. To be sure, it’s easier now than ever before due to the help of computers: physical records are increasingly being scanned and indexed into computer systems, enabling scholars to find photos and documents by browsing on a screen or even by conducting keyword searches. And of course, there are countless geneology databases on the Internet (most significantly by the Mormons who have a theological interest in cataloging the ancestry of pretty much everyone).

But what makes this especially exciting to me is the way the Internet and other new technologies will accellerate and empower this research so that, within the next decade or so, just about anybody will be able to view their own family histories as complete, thorough narratives, and even read documents about and view photographs of their distant ancestors, all at the click of a mouse.

Eigenfaces.

Imagine this: Face recognition technology, which is by the way rapidly reaching commercial maturity, unleashed on a massive database of scanned photographs, indexing those images based on who the people depicted are (if the names are known) or indexing them by their general facial “signature” (if the names are unknown).

I could use such a database to, say, find a photo of my great grandmother by simply entering her name. Or, even better, I could take a photo of my great-grandfather, scan it, submit its “signature” as a kind of “search term”, and then find a photo of him I may never have seen before. If this photo contains other people, I could do more searches and research into who they are, and perhaps learn about a long-forgotten grand-uncle who was a notorious bank robber.

This is something just about anyone would want and could benefit from. Like the celebrities in the PBS series, we could all use the Internet to easily (and cheaply) learn volumes about where we came from and who we are. Apparently there’s already at least one company making the connection between face recognition software and geneology.